Let's continue to use my six-step ©Follow Your Eyes Method in order to see what these artists were really up to.

3. Follow Your Eyes to identify the focal points along the visual path over the surface of the picture plane.

As you can see from the diagram of the Caravaggio painting below left, our eyes begin their path with the fully lit up-turned face (1) of the woman in the upper right corner. Her face is flanked by her wing-like open arms with fingers spread wide. The repetition of oval face shapes draws us to the Mother Mary (2), her down-turned face encircled by her white headdress. We follow the direction in which Mary looks to her outstretched hand appearing from behind the faces of the men (3) carrying Christ’s body. The men look downward and we follow their gaze to the face of Jesus (4). The intense value contrast between Christ’s arm and shroud against the dark background imply a line dropping downward to Christ’s hand grazing the tomb’s stone slab (5). Here at the bottom of the picture plane, our eyes are virtually halted by the chiaroscuro (literally light-shadow) of the stone’s vertical edge. But the repetition of arcs in Christ’s arm, the shroud cradling his hip, and the profile of feet and ankles (6) sweeps our eyes upward to the right to the feet of Jesus.

3. Follow Your Eyes to identify the focal points along the visual path over the surface of the picture plane.

As you can see from the diagram of the Caravaggio painting below left, our eyes begin their path with the fully lit up-turned face (1) of the woman in the upper right corner. Her face is flanked by her wing-like open arms with fingers spread wide. The repetition of oval face shapes draws us to the Mother Mary (2), her down-turned face encircled by her white headdress. We follow the direction in which Mary looks to her outstretched hand appearing from behind the faces of the men (3) carrying Christ’s body. The men look downward and we follow their gaze to the face of Jesus (4). The intense value contrast between Christ’s arm and shroud against the dark background imply a line dropping downward to Christ’s hand grazing the tomb’s stone slab (5). Here at the bottom of the picture plane, our eyes are virtually halted by the chiaroscuro (literally light-shadow) of the stone’s vertical edge. But the repetition of arcs in Christ’s arm, the shroud cradling his hip, and the profile of feet and ankles (6) sweeps our eyes upward to the right to the feet of Jesus.

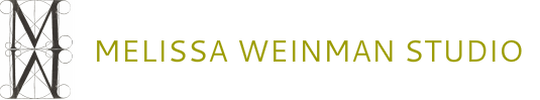

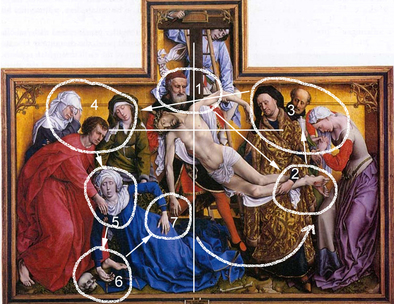

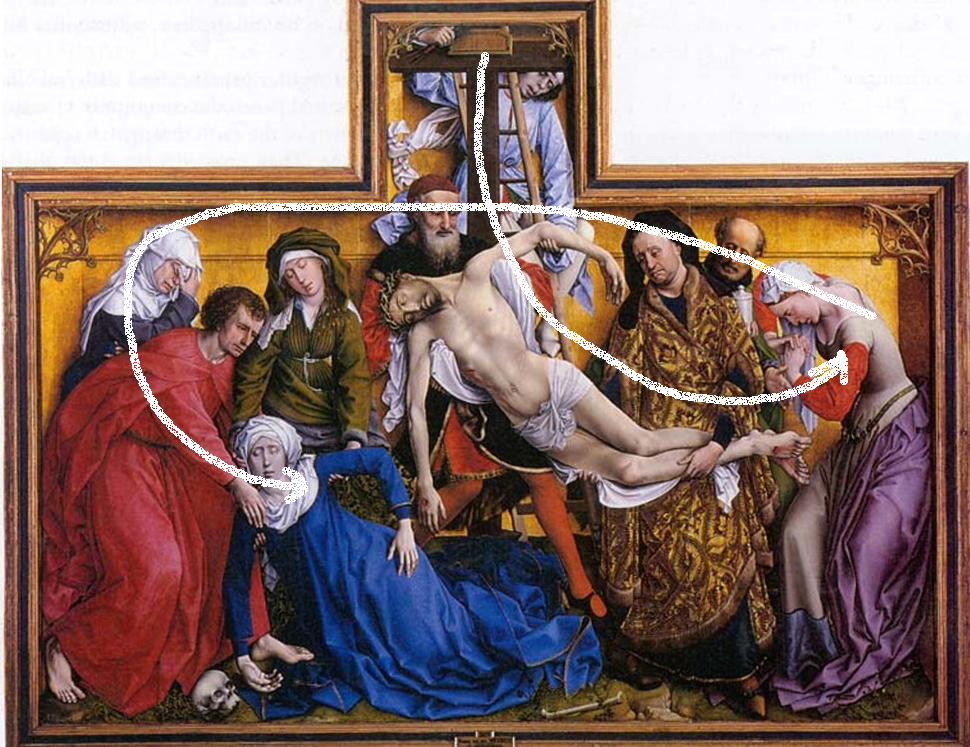

The focal points in Van der Weyden’s panel are densely packed groups of objects. In this strongly symmetrical composition it is not surprising to find our eyes begin to focus on the center of the painting where the stem of the cross meets Christ’s body (1). From here we follow the light shape of the body to the center right where hands carry his feet (2). The arc of the body continues through the feet along the red sleeve and shoulders of the woman on the far right. Her face and that of two others form a focal group (3). Their heads are aligned with the horizontal band in the gold backdrop which guides our eyes leftward following the direction in which the group faces. Traversing the panel past our initial focal point we arrive at another focal group, the three faces on the far left (4). The figures gesture downward to support the Mother Mary (5), whose arm hangs limp among yet another focal group: a skull, Mary’s hand, and a man’s bare foot (6). The objects form an implied diagonal that points our attention to Mary’s other hand, dangling and almost touching the pierced hand of her son (7).

4. Note focal points, if any, that lead your eye on a path back into the illusory space. Space is often a metaphor for time. The lack of space might indicate a momentary or immediate event.

Neither of these paintings depicts a deep space. Both scenes take place in the foreground in close proximity to the viewer, suggesting an event happening in the present. The figures are barely contained by the picture plane and because these paintings are large and have quite similar dimensions the figures appear nearly life-size.

5. Identify the two visual paths and interpret their configuration, as well as information revealed at the focal points.

We need only identify the visual paths over the surface of the picture plane as these paintings have no middle ground or background.

Caravaggio’s Deposition has a visual path of descent from right to left, suggesting a part of the story that is not literally depicted by a cross. Even though the space is shallow, his visual path alludes to the immediate past event of taking the body down from the cross and the struggle involved in it. What we see depicted in the present is the lowering of Christ’s body into the tomb as indicated by the dark recess below the stone slab.

Unexpectedly, the visual path does not end here but follows an upward arc to the right. Movement to the right flows more naturally and even though we might sense some strain in the upward nature of it, we sense momentum behind it as if our eyes follow a swinging pendulum. Is the fulcrum of it Christ’s hip or the elbow that protrudes directly toward us in the center of the picture? What could Caravaggio be saying here? Not only has he alluded to the past, painted the present, but he has also suggested the future. The upswing of his visual path alerts us to the imminent resurrection of the body.

Even though Caravaggio did not depict the cross it is embedded in the composition. Although secondary to the oval shape of the visual path, a cross is formed by a horizontal line implied by Mary’s outstretched hand, the heads of the men, the man’s protruding elbow, and the horizontal shadow of his cloak leading to Mary’s other out-stretched hand. This horizontal line is intersected by a vertical line implied by the vertical edge of the tomb stone, Christ’s wrapped hip, the head above it, Mary’s face, and the hand above her head. The suggested cross aids the viewer’s identification of the main figure as Christ Jesus.

Van der Weyden’s Descent has a visual path that descends from the top center, turns right and then back to the left crossing itself to the far left, ending in descent. Trace the path with your hand. I did, and as I did I had this odd feeling and thought to myself, "Doesn't it remind me of a gesture I have seen people make with the hand?" It reminds me of the path one makes across the heart in the Christian tradition of “making the sign of the cross” or “crossing oneself” for protection or in prayer.

The descent from focal group (4) to Mother Mary in blue is the tail end of our visual path, but not diminished by its location outside of the implied cross. In fact, we are drawn to three focal areas on Mary, which create a secondary path in the composition. First we see Mary’s face with her eyes shut and the pallor of her skin more ashen than any other including Jesus. Has her grief killed her? We follow her arm down to her hand and the skull (6), another allusion to death. Finally, our eyes rest on her other hand forming a focal group with the hand of her son (7) suggesting they have joined hands in death.

It seems that Van der Weyden intended to make a painting about the pain of grief, mortality, and death. The T shaped cross at the top of the long horizontal format acts like a plunger, pushing downward as if to compact and intensify the pain of death among those bound to this earth plane. Our eyes make the sign of the cross, a subconscious sacred gesture, as we witness the tragedy before us.

6. Check your interpretation against your initial impression. Your interpretation will be an expanded and deeper version of your original impression.

Though we knew both paintings depicted the same subject and evoked feelings of grief, we now see clearly how different compositional approaches led us to different conclusions about death. While Van der Weyden’s composition seems to be about Mary and the devastation of her grief, Caravaggio’s composition suggests flight and the hope of resurrection.

4. Note focal points, if any, that lead your eye on a path back into the illusory space. Space is often a metaphor for time. The lack of space might indicate a momentary or immediate event.

Neither of these paintings depicts a deep space. Both scenes take place in the foreground in close proximity to the viewer, suggesting an event happening in the present. The figures are barely contained by the picture plane and because these paintings are large and have quite similar dimensions the figures appear nearly life-size.

5. Identify the two visual paths and interpret their configuration, as well as information revealed at the focal points.

We need only identify the visual paths over the surface of the picture plane as these paintings have no middle ground or background.

Caravaggio’s Deposition has a visual path of descent from right to left, suggesting a part of the story that is not literally depicted by a cross. Even though the space is shallow, his visual path alludes to the immediate past event of taking the body down from the cross and the struggle involved in it. What we see depicted in the present is the lowering of Christ’s body into the tomb as indicated by the dark recess below the stone slab.

Unexpectedly, the visual path does not end here but follows an upward arc to the right. Movement to the right flows more naturally and even though we might sense some strain in the upward nature of it, we sense momentum behind it as if our eyes follow a swinging pendulum. Is the fulcrum of it Christ’s hip or the elbow that protrudes directly toward us in the center of the picture? What could Caravaggio be saying here? Not only has he alluded to the past, painted the present, but he has also suggested the future. The upswing of his visual path alerts us to the imminent resurrection of the body.

Even though Caravaggio did not depict the cross it is embedded in the composition. Although secondary to the oval shape of the visual path, a cross is formed by a horizontal line implied by Mary’s outstretched hand, the heads of the men, the man’s protruding elbow, and the horizontal shadow of his cloak leading to Mary’s other out-stretched hand. This horizontal line is intersected by a vertical line implied by the vertical edge of the tomb stone, Christ’s wrapped hip, the head above it, Mary’s face, and the hand above her head. The suggested cross aids the viewer’s identification of the main figure as Christ Jesus.

Van der Weyden’s Descent has a visual path that descends from the top center, turns right and then back to the left crossing itself to the far left, ending in descent. Trace the path with your hand. I did, and as I did I had this odd feeling and thought to myself, "Doesn't it remind me of a gesture I have seen people make with the hand?" It reminds me of the path one makes across the heart in the Christian tradition of “making the sign of the cross” or “crossing oneself” for protection or in prayer.

The descent from focal group (4) to Mother Mary in blue is the tail end of our visual path, but not diminished by its location outside of the implied cross. In fact, we are drawn to three focal areas on Mary, which create a secondary path in the composition. First we see Mary’s face with her eyes shut and the pallor of her skin more ashen than any other including Jesus. Has her grief killed her? We follow her arm down to her hand and the skull (6), another allusion to death. Finally, our eyes rest on her other hand forming a focal group with the hand of her son (7) suggesting they have joined hands in death.

It seems that Van der Weyden intended to make a painting about the pain of grief, mortality, and death. The T shaped cross at the top of the long horizontal format acts like a plunger, pushing downward as if to compact and intensify the pain of death among those bound to this earth plane. Our eyes make the sign of the cross, a subconscious sacred gesture, as we witness the tragedy before us.

6. Check your interpretation against your initial impression. Your interpretation will be an expanded and deeper version of your original impression.

Though we knew both paintings depicted the same subject and evoked feelings of grief, we now see clearly how different compositional approaches led us to different conclusions about death. While Van der Weyden’s composition seems to be about Mary and the devastation of her grief, Caravaggio’s composition suggests flight and the hope of resurrection.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed