To continue our discussion of the psychology of repetition, we must acknowledge that repetition is at work before we even recognize the subject of an image.

Let’s consider something that happens subconsciously in the first second we look at a painting or drawing. We notice the frame.

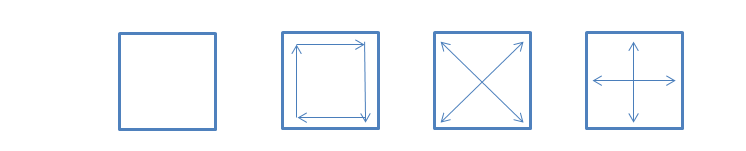

Remember that our eyes are always scanning imagery looking for something familiar, something we recognize. The very first thing we comprehend is the shape of the frame. Look at the square below. The right angles of the corners are distinguishing features and familiar. The repetition of right angles draws us from one to the next. In a fraction of a second our eyes take in all four corners. In the sweep from one to the next we notice the sides of the frame that connect them: two verticals and two horizontals. The sides being of equal length, we recognize the shape as a square.

The arrows represent the probable paths that our eyes take as they scan the image. What do you suppose happens where paths cross or meet? Such intersections create focal points.

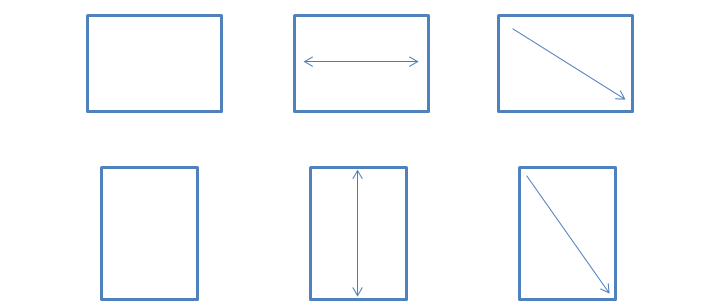

Now look at the rectangles below. These are traditional shapes for compositions. The vertically oriented rectangle is usually used for portraiture. The horizontal one is commonly used for everything else: landscape, still life, and narrative depictions.

Let’s consider something that happens subconsciously in the first second we look at a painting or drawing. We notice the frame.

Remember that our eyes are always scanning imagery looking for something familiar, something we recognize. The very first thing we comprehend is the shape of the frame. Look at the square below. The right angles of the corners are distinguishing features and familiar. The repetition of right angles draws us from one to the next. In a fraction of a second our eyes take in all four corners. In the sweep from one to the next we notice the sides of the frame that connect them: two verticals and two horizontals. The sides being of equal length, we recognize the shape as a square.

The arrows represent the probable paths that our eyes take as they scan the image. What do you suppose happens where paths cross or meet? Such intersections create focal points.

Now look at the rectangles below. These are traditional shapes for compositions. The vertically oriented rectangle is usually used for portraiture. The horizontal one is commonly used for everything else: landscape, still life, and narrative depictions.

The horizontal rectangle sends our eyes scanning in a lateral motion. The vertical one tends to draw our attention from the top to the bottom. Here’s where it gets interesting. Our brains are able to look at an image with both an environmental and a retinal orientation to the picture plane. These are terms used by Rudolf Arnheim in his classic, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye. Specifically, with an environmental orientation one reads gravity into the pictorial space as if the picture plane were a picture window. With retinal orientation one perceives the flatness of the picture plane as if it were the frame around a table top, where there is no top nor bottom.

As we consider the rectangle, our environmental perception usually leads us from the upper regions to the lower. When combined with our western perceptual tendency to read the picture plane from left to right, our eyes follow a diagonal path from upper left to lower right, unless focal points in the composition deter our eyes from this path, as the rectangles on the above right illustrate.

Next time we will learn why it is important for artists to be intentional about the shape and orientation of their compositions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed